Hank Bath: No Dempsey, but no fairy tale, either

By Pete Ehrmann

Archie Moore once famously said of Kearns, “Give him 500 pounds of steel wool and he’ll knit you a stove.” With Bath in tow, Kearns got right to work…

“I had to start looking for some more fighters. I found them, too, even if some of those I won’t bother mentioning hardly deserved the name. However, I handled guys like Roscoe Toles, Jimmy Adamick, and Lorenzo Pack, which at least kept the wolf from the door.”

That’s Jack “Doc” Kearns in his autobiography, “The Million Dollar Gate” (“the lusty, gutsy adventures of the greatest fight manager of them all”), talking about the barren stretch in his career during the 1930s when his salad days calling the shots for Jack Dempsey and Mickey Walker were over and he was more than a decade away from doing the same for Joey Maxim and Archie Moore.

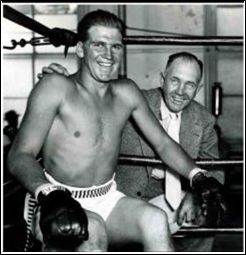

Toles, Adamick, and Pack were heavyweights good enough, with Kearns’ help, to crack the Top 10. But missing from the list and mentioned nowhere else in Kearns’ book is Hank Bath.

That’s odd because for a while in the ‘30s it seemed that the loquacious Kearns talked about little else than the young heavyweight KO artist from Colorado — Dempsey country — who Kearns insisted was better than the Manassa Mauler and would have no problem beating then-heavyweight champion Jimmy Braddock and top contender Joe Louis on the same night.

Bath never fought either of them, and his comet-like rise fizzled after some sensational headlines and typical Kearns-generated controversy. But he ought to have gotten at least a footnote in Kearns’ memoir for the fighter’s role in helping Kearns break the ice with Dempsey after a bitter 13-year estrangement.

1940s big band leader Benny Goodman was the most famous person to come out of Fort Morgan, Colorado, but not even he put together a string of hits like the one that brought Edward Henry Bath to Kearns’ attention. One of 15 children in his family, Bath, born one hundred years ago this October 18, grew up on a ranch in the northeast part of the Centennial State and learned the rudiments of boxing from his older brother, Jake Jr., who’d had a few nondescript pro bouts in the mid-1920s.

The six-foot, 185-pound Bath turned pro in 1934, and in about a year’s time put away all of his 21 opponents. The opponents were as unknown and forlorn as the venues — mining and farming outposts like Greeley, Sterling, and Fort Morgan; and even Greeley promoter J.W. Norcross was unimpressed until Bath scored his 20th KO in a row against Dutch Dohner on July 23, 1935.

“Beautifully sun-tanned, Bath threw his usual caution to the winds from the opening round and hammered into the beetle-browed Dohner with sledgehammer fists,” reported a newspaper account of the fight. “In the first round Dohner had a bloody nose to show for his windmill swinging and at the end of the third” — when the fight was stopped — “his face was one bloody mass.”

Declared Norcross of the blond 19-year-old winner: “Bath is going places.”

About three months later, Bath did, speeding out of Colorado on the Doc Kearns Express. Kearns had contacts everywhere he milked constantly to keep that dreaded wolf at bay, and when word reached him about the Fort Morgan kid who was knocking out everybody he fought, Kearns made a beeline for the Bath Ranch and used the talent for spinning dreams that 13 years earlier had prompted the city of Shelby, Montana, to bankrupt itself helping Kearns promote the Dempsey-Tommy Gibbons heavyweight title fight to convince Hank that with the greatest fight manager of them all in the driver’s seat Colorado would soon have its second heavyweight champion of the world.

Archie Moore once famously said of Kearns, “Give him 500 pounds of steel wool and he’ll knit you a stove.” With Bath in tow, Kearns got right to work. They headed for the West Coast by way of Arizona, where in Phoenix and Tucson the new “Colorado Thunderbolt” added two more KOs to his streak, which according to Kearns gave Bath 34 in a row.

By the time they landed in Los Angeles about two weeks later it was down to 31. Kearns’ imprecise arithmetic didn’t raise eyebrows, but when Doc claimed that his new, better Dempsey could clobber Braddock and Louis with barely a breather in-between, that got a lot of attention.

“Mr. Kearns, you’re a liar!” huffed one outraged columnist. But most reporters were eager and grateful for the always colorful copy ladled out by the fight manager whose words, wrote Oscar Fraley, Kearns’ collaborator on his autobiography, “came out with the flowery grandiloquence of a circus ringmaster, the persuasive ease of an evangelist, or the impact of a triphammer, depending on the case.”

Said the man himself: “I was convinced that people wanted to be sold a bill of goods as long as it didn’t do them any harm but merely heightened their anticipation and enjoyment of an event. Thus it was that I became a dealer in adult fairy tales.”

Mother Goosed by Kearns, so many fans turned out to ogle his new heavyweight wonder that the 11,000-seat Olympic Auditorium couldn’t hold all of them when Bath made his Los Angeles debut on November 7, 1935. Thousands were turned away at the door — and when they read in the newspapers the next day about what they missed, maybe they celebrated their good luck with a nip or two.What Terris Hill — “the ferocious Madagascar Negro,” according to the L.A. Times — had been celebrating in his dressing room at the Olympic before he was to head out to the ring and fight Hank Bath in the six-round “special attraction,” nobody knew. But he was definitely blotto when the boxing commission doctor made his pre-fight visit, and the frantic commissioners scratched him and substituted a fighter named Ralph Norwood.

Trouble was, Norwood had been Bath’s sparring partner all week and was knocked down by him several times in the gym. There’d even been a picture in the paper of him hitting the deck in a sparring session with Bath.

Nevertheless, Norwood got the call to pinch-hit for Terris, and picked up where he’d left off with Bath. He was floored three times in the fight that lasted 40 seconds.

There was considerable booing at the Olympic and in the papers the following day. Some went so far as to suggest that it was Kearns who supplied the hooch that diluted the ferocity of Terris Hill. Writing in The Ring, Eddie Borden, while acknowledging Kearns’ “flair for exaggeration,” said the blame for the fiasco belonged solely with the boxing commission for choosing Norwood to sub for Hill over Kearns’ own objections.

The California commission’s solution was to match Bath and Terris Hill five days later in another “special attraction” bout at the Olympic, and donate 15% of the proceeds to charity. Bath got the decision in the far from scintillating contest. “Hill did not appear to be trying, and Bath never came close to connecting with anything that appeared like a knockout punch,” wrote Bill Potts in the Times. “By holding his own with Bath without half-trying, Hill exploded all the widespread theories of invincibility woven about the Colorado youngster. He shows promise, but that’s all. The next stop will probably be the ‘sticks’ for the Bath entourage where the knockout record will take up where it was interrupted by Hill.”

Maybe they thought he was just drunk again, until it turned out that the mumbling coming from Hill after the fight was caused by a jaw broken in three places by Bath’s punches. So instead of the sticks it was back to the Olympic, where two weeks later Hank knocked out Butch Rogers in three to get things pointed in the right direction again.

That direction was east — New York. Madison Square Garden.

The opponent selected for Bath’s coming-out fight in boxing’s greatest venue on January 10, 1936, was Clarence “Red” Burman, who’d lost two of 18 pro fights. But what really made it a compelling match-up was that at the time Burman was managed by Jack Dempsey.

Kearns and Dempsey had been bitter enemies since their acrimonious break-up in 1923, when Dempsey was still champion. Since then they had carried on what sportswriter John Lardner called “the most gorgeous grudge in the prizefight industry.” Mostly it was Kearns’ doing. He was, Lardner wrote, “a cold, stern fellow with a long memory.”

Now the former pals would be going up against each other in the ring, albeit as seconds for their respective tigers. Garden promoter James J. Johnston took full advantage of the situation. “Across the entrance to Madison Square Garden hangs a sign advertising ‘Jack Dempsey vs. Jack Kearns’ in letters a foot high,” reported sportswriter Stuart Cameron. “Underneath, in letters about three inches high, are the names of their fighters.”

Kearns knitted away furiously. “You may laugh when I tell you this, but Hank Bath has greater possibilities than Dempsey ever had,” he told reporters. “He’s just a baby now, and has been off the farm only four months, but he has everything to make a champion. All he needs is a little time and experience and he’ll go farther than Dempsey ever did.”

But two days before the fight, the New York boxing commission pulled the plug on it, refusing to license Bath and Kearns on the grounds that “two of (Bath’s) three fights in California were questionable” — the ones against sparring partner Norwood and Butch Rogers. (Rogers was suspended by the California commission after the Bath fight, reportedly because he had entered the ring with a bad right hand.)

So Kearns took Bath to Chicago, and on January 28 he lost for the first time, a close decision to Billy Treest. Bath was floored three times in the 10-rounder, “but left the ring on the receiving end of a rousing ovation,” reported the Associated Press. “The Apollo-like Colorado youngster displayed an abundance of courage, perfect physical condition and a terrific punch in his right hand.”

That qualified him to fight Burman at Chicago Stadium about two weeks later, and 10,000 excited customers turned out to see the bitter antagonists go at it. And Bath vs. Burman, too.

Kearns and Bath were first in the ring. When Dempsey and Burman followed, the ex-champ walked up to his onetime pilot, stuck out his hand and said, “How’s tricks, Doc?” To the disappointment of just about everyone, Kearns shook Dempsey’s hand and replied, “OK, Jack.” They even posed together for photographers, “and appeared to do it with a minimum of effort,” noted the AP.

The fight was anti-climatic and dull. Burman won a unanimous decision.

Less than a month later, newspapers reported that Lorenzo Pack was Kearns’ latest new Dempsey.

Hank Bath returned to Colorado and fought sporadically over the next five years, losing more than winning. He owned a bar for a while in Fort Morgan, and did more ranching. He died on March 12, 1996.

He wasn’t Dempsey redux, but don’t tell that to the three guys in their 20s who made the mistake of hassling Hank and his brother Jake in a Denver bar one day. When the cops showed up and found the three punks out cold on the floor, they told the Baths — ages 68 and 77, respectively — to just go on home.

Pete Ehrmann’s work as a boxing journalist/historian over the past 40 plus years speaks for itself. Pete’s first by-line appeared in The Ring magazine at age 14, and ever since he has written about the sport (and other matters) for newspapers, magazines and websites. Pete has been a valuable member of the IBRO since April 2013.