A Look Back at the Career of former Middleweight Contender Rory Calhoun

By Dan Cuoco

Rory Calhoun was born Herman Calhoun on September 29, 1935, in McDonough, Georgia. He was the fifth of seven boys and four girls. As a professional he fought out of White Plains, NY. He campaigned from 1954 until 1962 and thrilled fight fans with a fearless and exciting two fisted attack. He was a fixture on the Friday Night Fights, appearing 27 times. Rory was a world ranked middleweight contender from September 1956 until March 1961, his highest ranking number 3. During his career he compiled a record of 45-15-2 (21) and defeated outstanding fighters such as Dick Tiger, Rocky Castellani, Joey Giambra, Hank Casey, Ralph (Tiger) Jones, Bobby Boyd, Randy Sandy, Charley Cotton, Willie Vaughn, Jerry Luedee, Charley Salas, Johnny Sullivan, Angelo DeFendis, Germinal Ballarin, Franz Szuzina, Jackie LaBua and Yolande Pompey. He also fought outstanding fighters such as Joey Giardello, Henry Hank, Spider Webb, Bobo Olson, Florentino Fernandez, Eddie Cotton and Jimmy Ellis. He died of liver failure in Hollywood, CA on February 15, 1988 at the age of 53.

Rory Calhoun was born Herman Calhoun on September 29, 1935, in McDonough, Georgia. He was the fifth of seven boys and four girls. As a professional he fought out of White Plains, NY. He campaigned from 1954 until 1962 and thrilled fight fans with a fearless and exciting two fisted attack. He was a fixture on the Friday Night Fights, appearing 27 times. Rory was a world ranked middleweight contender from September 1956 until March 1961, his highest ranking number 3. During his career he compiled a record of 45-15-2 (21) and defeated outstanding fighters such as Dick Tiger, Rocky Castellani, Joey Giambra, Hank Casey, Ralph (Tiger) Jones, Bobby Boyd, Randy Sandy, Charley Cotton, Willie Vaughn, Jerry Luedee, Charley Salas, Johnny Sullivan, Angelo DeFendis, Germinal Ballarin, Franz Szuzina, Jackie LaBua and Yolande Pompey. He also fought outstanding fighters such as Joey Giardello, Henry Hank, Spider Webb, Bobo Olson, Florentino Fernandez, Eddie Cotton and Jimmy Ellis. He died of liver failure in Hollywood, CA on February 15, 1988 at the age of 53.

In an interview with Fred Eisenstadt in the December 1957 issue of The Ring magazine, Rory told Fred: “I was a pretty rough kid in my school days. I was always eager to fight. I can’t explain exactly what prompted me to go after kids I didn’t get along with. I simply had the urge to beat up anybody I didn’t get along with. I know it sounds awful but that’s the kind of boy I was until I reached the age of sixteen – then I calmed down and behaved liked the average lad.” Calhoun further stated: “Believe it or not, fighting in no way interfered with my school work. I was a fairly bright student. My father, Reverend Willie M. Calhoun, being a minister – tenant farmer, our family kept moving to various towns around the state of Georgia – and so I had to shift to different schools and I beat up different kids all the time. And no matter how often my father belted the devil out of me for fighting, it failed to curb my combative tendencies.” [1]

During his senior year at Booker T. Washington High School in Atlanta, GA his natural love of fighting and his desire to make boxing a career prompted him to join the local YMCA and register for boxing. Under the direction of Aaron Watson he started to learn his craft. He engaged in six amateur contests before graduating from high school. After graduation he moved to New York to live with relatives in the suburb of White Plains to further his boxing career.

In White Plains he worked as a pin-boy in a bowling alley and joined the local Police Athletic League boxing program under the direction of boxing coaches Joe Callahan and Mickey Donnelly. After winning 23 of 25 amateur contests he decided to turn pro under the management of Frank Bachman and his son Alvin. Frank Bachman had managed ring greats Maxie Rosenbloom, Bob Olin and Lew Jenkins. The Bachman’s put Calhoun under the tutelage of famed trainer Charlie Goldman. Frank Bachman changed Calhoun’s name to ‘Rory’ after actor Rory Calhoun shortly before his pro debut.

Rory’s pro education developed steadily and impressively under Goldman’s guidance. He started his pro career on September 13, 1954 winning a four round decision over John Gibson at the Eastern Parkway Arena. He followed this with three decision victories over undefeated prospects Angelo DeFendis (4-0-0), Hardy Smallman (4-0-0), and Jerry Luedee (9-0-0). In 1955 Rory went 12-0 with 8 KO/TKOs. He started the year off with a fourth round stoppage of 60 fight veteran Tommy Dixon and a first round knockout of tough club fighter Mike Bruce. His next two fights were decisions over Don Bryant and undefeated Mel Collins (8-0-0), before travelling to Philadelphia to engage in his first eight rounder where he won a decision over tough journeyman Al Hauser.

After stopping Stan Micheaux in the sixth round at St. Nick’s Arena in New York Rory suddenly ran out of opponents willing to get in the ring with him. So the Bachman’s decided to take their charge to California where he engaged in six fights winning five by kayo/stoppage. All six fights took place at the legendary Olympic Auditorium. His biggest victories were a first round knockout of Sonny Gil in his first ten round main event, a third round knockout over experienced Clifton Lester and a sensational ninth round stoppage over Charley Salas. This was the only time in Salas’ 202 fight career he failed to go the distance. Salas retired in 1957 with a record of 136-52-13 (52). The victory over Salas gained the 16-0-0 (8) Calhoun national recognition and promoters everywhere wanted to book him.

With leverage on their side the Calhoun team headed back to New York. On January 22, 1956 he headlined his first main event in New York and defeated tough Jerry Leudee who had won nine straight since Rory had handed him his only previous defeat on November 26, 1954. Next, he stopped hard-punching Angelo DeFendis in 6 rounds. Like Luedee before him, this was only DeFendis second defeat, both to Calhoun in 14 fights.

With leverage on their side the Calhoun team headed back to New York. On January 22, 1956 he headlined his first main event in New York and defeated tough Jerry Leudee who had won nine straight since Rory had handed him his only previous defeat on November 26, 1954. Next, he stopped hard-punching Angelo DeFendis in 6 rounds. Like Luedee before him, this was only DeFendis second defeat, both to Calhoun in 14 fights.

The fight that boosted Rory’s prestige was against Jackie LaBua before a national TV audience in his TV debut. The 23-year-old LaBua was a busy and willing fighter, but his punches couldn’t match Rory’s power. Rory was never in serious trouble and was the aggressor throughout the fight. Early in the fourth round, LaBua was cut in the corner of his left eye by an overhand right. He rallied after that punch, and then was dropped by a right to the jaw for a mandatory eight count. Rory was well ahead on points in the eighth round but lost it because of two low blows. He outpunched LaBua in the ninth and had him rocking on his heels in the tenth. After the fight, LaBua stated: “I’ve been in with some pretty tough fighters but none ever hurt me like that Calhoun. He’s strong as a bull, and once he learns to shorten his punches he’s going to be an even better fighter.” [2]

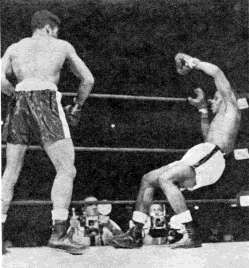

Rory looked even more sensational in his next fight when he scored an impressive first round technical knockout over a shifty fighter named Randy Sandy. Rory only needed 2:42 to subdue Sandy. In the first minute of the fight Sandy missed a left and Rory countered with a powerful right on the point of the chin and floored him. Sandy arose at the count of three and took the mandatory eight count. Rory moved in quickly, drove Sandy into a corner with a flurry of body blows and dropped him for an eight count with a thunderous right uppercut. Then a right to the body sent Sandy sprawling to the canvas for the third knockdown causing Referee Ray Miller to stop the fight.

Next up was a national TV date with Willie Vaughn. Vaughn got off to a rough start, losing the first four rounds, and suffered a knockdown in the third. Vaughn gave a fine boxing exhibition in the fifth, sixth and seventh rounds. In the eighth he tried to trade punches with Rory and that proved a mistake. Each landed a right simultaneously, but Rory’s carried the greater force, sending Willie to the canvas for a nine count When action resumed, Rory rushed Vaughn and sent him to the floor again with two rights to the head. He was up at two but had to take an eight count. Rory sprang at him and tagged him with a long right causing Referee Ruby Goldstein to stop the fight.

Rory faced Toledo, Ohio’s tough 25-year-old Charlie Cotton in his next start winning a hard fought 10 round split-decision. Cotton was coming off two decision victories over Joey Giardello. Rory reached Cotton repeatedly with stiff left hooks and had him in trouble twice. Cotton, an excellent counter-puncher, shook Rory twice in the fifth round. In the eighth round Rory had Cotton in real trouble. Cotton was able to weather the storm but could offer little in retaliation for the remainder of the fight.

Ducking no one Rory faced the dangerous Spider Webb (15-1-0, 11 KOs) in his next start, a nationally televised fight at Chicago Stadium.

Webb was a fast rising star fresh off an impressive decision over Holly Mims and sensational knockouts over Bobby Boyd and Jimmy Martinez. Webb snapped Rory’s 23-fight unbeaten streak by unanimous decision in a thrilling ten-round bout. Webb, a 9-5 underdog, took Rory’s best shots and survived an apparent third round knockout defeat. In that round, he slugged Webb into a corner with a right to the jaw. Thinking Webb would sink to the floor off the ropes, Rory turned and walked away. But Webb bounced right back and weathered the round. The turning point appeared to be the eighth round when Rory hurt Webb with one of his thunderous left hooks. However, Webb rallied with a flailing sharp right hand and stung his foe. After that, Rory knew he had to score a knockout to win and pulled out all stops in a blistering final round, but Webb stayed beyond range. Referee Joey White voted 46-44; Judges Howard Walsh and Louis Capparelli voted 45-44, all for Webb. Alvin Bachman stated after the fight, “My father, trainer Charlie Goldman and I did a slow burn in the corner, watching him blow an opportunity to polish off a real name fighter, but that’s something that cannot be helped.”

Rory bounced back by stopping England’s hard punching Johnny Sullivan in 8 rounds, Leroy Oliphant in 5 rounds, outpointing former victim Charlie Cotton in 10, and stopping Georgia Kid in 6 rounds.

On May 17, 1957, Rory faced fellow middleweight contender Joey Giardello at Cleveland Arena. Giardello (70-14-6) used his experience to good advantage to win a close split decision in a tough ten-rounder. Giardello accumulated an edge in the early rounds and then staved off Rory’s rally in the last half of the bout when he unleashed a wild-hooking attack to body and head.

A month later, Rory, now rated fifth, was in the ring against third rated middleweight contender Joey Giambra (50-4-1). Neither fighter lost any prestige as title challengers as they battled to a draw in a torrid 10-round bout at the War Memorial Auditorium in Syracuse, New York. Giambra took charge early in the furious struggle but Rory came back so strongly in the later rounds that Joey had to take the final round to avoid losing the verdict. It was a close, exciting fight from the opening bell. Rory did most of the forcing in every round but he was given a boxing lesson by the cool, fast moving Giambra. All 10 rounds were thrillers but the finale was a classic. Realizing the fight was close, both threw punches for the entire three minutes with Joey scoring more effectively and more often. Despite the fight’s ferociousness, neither fighter was hurt although Joey opened a cut over Rory’s right eye in the fifth round and reopened it in the frantic tenth round. Despite the draw, both fighters retained their high ratings.

Rory got back in the winners column as he rattled off four impressive wins to end 1957 on a high note. He won unanimous decisions over Germinal Ballarin, Joey Giambra, in their return match, Rocky Castallani and stopped Bobby Boyd in two rounds.

The win over Giambra was especially gratifying to Rory because it brought him closer to a title shot. Rory scored a decisive and unanimous decision over San Francisco’s adopted son Joey Giambra at the San Francisco Cow Palace. Giambra, a 2 ½-1 favorite took a sound beating before 8,786 fans. The bout was reasonably close for the first eight rounds, but Rory turned up the heat in the ninth to win going away. Rory had a big fourth round when he staggered Joey with a volley of overhand rights to the head. Giambra fought back gamely to take the fifth and sixth rounds, but in the ninth Rory unleashed a savage attack that had Joey rocking on his heels. Rory scored solidly with eight powerful uppercuts that hurt and befuddled Joey. The blows brought blood from Giambra’s mouth and nose and seemed to take the steam out of his countering punches. Rory’s left eye became puffy and bruised as early as the first round and was cut slightly in the fifth. However, trainer Charlie Goldman worked on it effectively between rounds and it never gave him any serious trouble. Rory punched well to the body throughout most of the fight and scored often with right-hand leads and stiff left jabs. Joey managed to stay in and land well to the head throughout the first eight rounds. He appeared fresh and ready to make a strong stand when the ninth round got underway. Joey agreed later that the uppercuts proved troublesome and that he didn’t expect Rory to start so fast. [3]

On November 22, 1957, Rory stopped Bobby Boyd in the second round at Madison Square Garden in a bizarre ending. Rory dropped Boyd with a right to the body and another right to the chin at the start of the second round. Boyd went down, staggered to his feet at five, fell against the ropes and bounced around the ring, as the count went to eight. Referee Al Berl extended his arms in a motion that about 2,499 of the estimated 2,500 fans understood to be the end of the bout. As Boyd started to his corner, Berl suddenly wiped off his gloves and waved the two into action. Rory clouted Boyd on the side of the head with a long right and down he went again. The count reached three before Berl positively stopped the fight. Everybody in Rory’s corner thought it was over the first time. So did the ringside press and the spectators. Boyd’s handlers claimed Berl had told them it was over. The rhubarb detracted from the performance of Rory who officially was credited with a TKO in 25 seconds of the second round. Boyd’s manager Bernie Glickman threatened to protest to the New York State Athletic Commission claiming Rory should have been disqualified, but referee Berl claimed that he asked Boyd if he was alright and that Boyd had his hands up when he told them to fight on. [4]

Rory’s four fight winning streak saw his stock soar again as he rose in the ratings to number three behind Ray Robinson and Gene Fullmer. Not one to sit on his laurels, Rory signed to meet the dangerous Spider Webb in a return bout in neutral San Francisco on January 20, 1958. He had been waiting fifteen months to get Webb back in the ring with him. He wanted the fight so badly he was willing to put his lofty rating on the line. Rory was heavily favored entering the bout. The cagey Webb was expected to start fast and then tire in the late rounds. But Rory came out blasting and had Webb on the floor for a nine count in the first round and again for another count of nine in the second. Webb looked through. Even when he remained on his feet in the third, he took a heavy body battering from Rory. In the fourth, the 9,332 fans in attendance found out what makes boxing the most thrilling of all sports. They saw one mistake in the form of a momentary opening change the entire complexion of the fight. Confident Rory wound up his left to deliver another hook. Webb let go a right that carried all his weight, and caught Rory coming forward. The punch hit him flush on the chin and he was on the floor in dire trouble. Rory just managed to rise at nine. It looked as if Webb had an open target, but Spider did not rush matters. He circled Rory, and then sent in a series of range finding jabs followed by a bombshell right which dropped Rory flat on his back. Referee Jack Downey immediately jumped in and halted the fight. [5]

A month later, Rory, now ranked sixth, accepted a tune up fight with Young Beau Jack in Revere, Massachusetts in preparation for a return match with Randy Sandy. He floored Jack twice in the second with left hooks to the jaw and finished him in the fifth with a left hook and right cross. A week later he had a difficult time winning a split decision over former knockout victim Randy Sandy at Mechanics Building in Boston before a crowd of 3,879. Rory relied mainly on a vicious right hand to raise his record to 33-3-1 (17 KOs). Sandy used his jab to advantage and was the faster fighter. But, Rory had Sandy in trouble in the first, sixth and ninth rounds. Sandy fared best in the fourth round when he scored with both hands. Most ringside observers agreed with the decision in Rory’s favor feeling that he scored often enough to deserve the decision.

Continuing his busy schedule, he stopped Yolande Pompey four weeks later in six rounds at Freedom Hall in Louisville Kentucky. Rory was well ahead on points when he landed an overhand neck-snapping-right seconds before the end of the fifth round. The ring physician halted the bout after Pompey complained of a neck injury.

On May 5, 1958, Rory met Joey Giardello in a rematch at the Cow Palace in San Francisco before a crowd of nearly 11,000. Giardello knocked Rory down twice in the early stages of the fight, and then hung on to gain a unanimous decision. Both fighters engaged in a savage brawl that included rabbit punches, hitting on the breaks, and low blows. Rory was dropped for a nine count in the fourth and a five count in the fifth. He held his own the rest of the way.

Ah, those were the days. Fighters didn’t dwell on disappointing losses for long. On June 25, 1958 Rory was again in the ring, this time in Chicago against former victim Bobby Boyd. Hometown favorite Boyd was hell bent on getting revenge for the stoppage loss he suffered in New York seven months earlier against Rory. Rory used a punishing body attack to gain a unanimous decision over Boyd leaving no doubt that his earlier win was no fluke. Boyd was knocked down twice, once in the second round and again in the ninth, each time by startling right hands to the head. But it was Rory’s continuous assault to the body that took the steam out of Boyd’s attack and slowed him to a walk in the late rounds.

The Boyd victory was followed by what may have been Rory’s most disappointing loss of his career – an upset decision loss to Gene “Ace” Armstrong on August 8, 1958. Armstrong (14-0-0) was making his first main event appearance in Madision Square Garden as well as his national TV debut. The light hitting Armstrong (one stoppage victory) sent Rory thudding to the floor just over two minutes into the fight when he landed a left hook to the chin. He got up at the count of four but took the mandatory eight count. Rory, still groggy, fought on after the bell. Armstrong floored him again in the second round when he fired a jolting left to the chin just as Rory missed with a short right. Again Rory took the mandatory eight count after rising at two. He got through the third without mishap, but in the fourth he was dropped again by a right-left combination. Once again he bounced up at a count of two and took the mandatory eight count. In the ninth round he went down for the fourth time. Armstrong was belaboring him with sharp combinations. He was so groggy and tired that he fell from a half-push, half-punch. Armstrong was too fast a puncher, too accurate and too clever for Rory who was forced into wild swings in an effort to hit his dancing, bobbing, darting foe. Rory was gracious in defeat. When asked by reporters about Armstrong’s lack of punching power, Rory rubbing his jaw responded: “He can punch real good. He sure surprised me.” [6] The loss dropped Rory to eighth in The Ring ratings.

Ten days later, Rory was back in the ring again, this time in Sherbrooke, Quebec where he stopped Hank Mercer in six rounds. Then, in October, he headed to Rochester, New York to take on rugged Franz Szuzina (45-20-14). Rory gained a unanimous ten-round decision by stalking the shorter Szuzina all the way. He piled up points at long range, successfully tied up Szuzuna in the clinches and won by a wide margin even though he lost one round for low blows.

The win over Szuzina earned Rory a nationally televised fight at Madision Square Garden against TV favorite Ralph (Tiger) Jones (46-23-4) on November 21, 1958. The unranked Jones, a 9-5 underdog, won a unanimous decision after Rory had been penalized his best round, the eighth, on a low-blow foul. Jones was awarded the verdict on a rounds basis, after Referee Ray Miller’s eighth round forfeiture ruling for a low left hook. Miller had warned Rory for low blows in the fifth. Jones forced the action as he marched forward persistently and he landed a lot of leather; but it was Rory who did the harder punching. Rory’s combined body-head slugging had Jones back on his heels or groggy in six of the ten rounds. A ringside poll of 14 sportswriters showed eight scoring the bout for Rory, five for Jones and one having it even. [7]

Rory exacted revenge on Tiger Jones less than a month later in Cleveland when they headlined Ed Bang’s 33rd annual Cleveland News Toyshop Fund at the Cleveland Arena. He won a close unanimous decision in a rugged affair. The win elevated Rory from ninth to eighth in The Ring ratings at the close of 1958.

Rory started 1959 off in grand fashion by stopping old rival Al Hauser of Philadelphia in the tenth round at the South Main Street Armory in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. In the final round, Hauser was dropped twice for eight counts by powerful rights to the chin. Hauser was on the ropes unable to defend himself when Referee Manny Gelb halted the fight at 1:17 of the final round.

In March 1959, Rory was offered a fight with former middleweight-champion Carl (Bobo) Olson. The 31-year-old former champion (75-10-0) was on the comeback trail fighting at light-heavyweight. He was on a modest three fight winning streak: Don Grant (TKO 7), Paddy Young (TKO 6), and Tommy Villa (TKO 5). They met on March 30, 1959 at the Cow Palace in San Francisco before a crowd of 11,246. Bobo outweighed Rory 174 ¼ to 168 ¼. Olson withstood Rory’s brutal body attack, dropped him once and staggered him twice to pound out a unanimous decision. Olson, known as a very good infighter, was outworked on the inside and opted instead to sharp-shoot with his right hand from the outside. These tactics worked effectively for him in the second, fourth, sixth and seventh. A left hook knocked Rory down for a five count in the seventh round, though Rory’s manager Frank Bachman argued that Rory had slipped. Olson tired badly in the last two rounds, and did little punching. Rory was penalized 2 points by Referee Pete Morelli for low blows in the first and third rounds. [8]

The loss dropped Rory out of The Ring’s top 10 ratings.

Unfazed by the loss to Olson, Rory accepted a fight with British Empire Middleweight Champion Dick Tiger who was making his American debut. Rory and Tiger went into their Madison Square Garden bout evenly rated. Tiger’s classy boxing enabled him to gain the early lead during the first four rounds. He mixed good hooks to the body with short chopping rights and lefts to the head. But Rory woke up after the fifth round and began to catch Tiger heavily to the body with right hooks. As soon as Tiger’s guard came down to halt the body blows, he shifted to the head with noticeable effect. Rory shook Tiger at the start of the sixth with two solid rights on the chin and before the round was over he had forced Tiger to clinch to save himself from real damage. Rory continued to blast away to the body and head through the next three rounds. Frequently he forced Tiger to back off from his solid punches to the chin in the eighth and ninth rounds. Rory’s sustained punching was over by the tenth round, and Tiger had the better of the final three minutes with a steady offense of sharp punching. And when the bristling scrap was over there was a decided difference of opinion among the three officials. The breakdown of the three cards resulted in a draw. Judge Bill Recht voted six rounds to Tiger, three to Rory and called one even. Judge Bill Frost’s card favored Rory five rounds to four with one even. The split vote left the ultimate decision to Referee Mark Conn. Conn saw the bout even all the way. He gave five rounds to each fighter. Then using New York State’s supplemental point system to decide close rounds, he voted five points to each man. The New York Times scorecard favored Rory, five rounds to four with one even. A poll of 12 ringside reporters also resulted in a standstill. Four favored Rory and four scored the bout even. [9]

They met again five weeks later in a nationally televised bout held at the War Memorial Auditorium in Syracuse. Rory came away with a split and disputed decision. The fight bore little resemblance to their exciting draw. The crowd of 1,320 booed and clapped for action at the end of the sixth, eighth and ninth rounds. Rory was the aggressor in the beginning and won the first two rounds, but then Tiger’s short, accurate combinations to the face began to find the mark. He seemed to have a solid lead from the fourth round on. Rory’s best offense was his slashing long rights and lefts to the body. But Tiger was far more accurate, scoring frequently with sharp uppercuts to the face, jabbing to halt Rory’s rushes, then shooting his own sharp right to the chin.

Rory stumbled in his next fight when he lost an upset majority decison to 22-year-old hot propsect Rudy Ellis (15-3-1) in Ellis’ hometown of Chicago. The hard-punching Ellis entered his first nationally televised fight on a hot streak with a decision victory over the dangerous Jesse Smith and knockout victories over veterans Jimmy Beecham, and Bobby Boyd. Ellis withstood Rory’s body attack with ease to win the decision. Rory was staggered in the third round when Ellis opened a two-fisted attack and took control. Rory was staggered again in the tenth when Ellis scored with a long overhand right early in the round. In both the third and tenth rounds it looked like Rory would not finish the round. But Ellis was careless with his follow-up punches. Ellis tried to score repeatedly with his right cross, but Rory covered up well and countered most blows. In the seventh both fighters squared off in the middle of the ring for a punching match which brought the crowd to its feet.

Rory took a step back from fighting the division’s iron and traveled to Montreal to keep busy. On November 2, 1959, he knocked out light-heavyweight Joey White in six rounds; and on November 30, 1959 he won a ten round unanimous decision over veteran journeyman Tony Masciarelli.

On February 5, 1960, Rory was back in New York headlining a card at Madison Square Garden against another young lion. This time it was 23-year-old Lowell, Massachusetts light-heavyweight Billy Ryan. Ryan, a protégé of Rocky Marciano, sported a record of 23-2-2, with 17 knockouts. Ryan went into the ring with a weight advantage of 6 ½ pounds: 171-164 ½. But there is no substitution for experience, and Rory had that in abundance. The result was a sound boxing lesson for Ryan and a unanimous decision for Rory. Ryan slipped to the canvas in the sixth round when his right ankle buckled. Referee Ruby Goldstein ruled it a knockdown and started counting. The crowd failing to see a punch booed. Goldstein later described Ryan’s trip to the canvas as the delayed effect of a heavy body punch. However, Ryan’s ankle appeared swollen in the dressing room. [10]

Three weeks later, Rory took on old rival Spider Webb at the Cow Palace in San Francisco. This was their third meeting. Like their first two fights, this was a free-swinging action packed bout. Webb was awarded a controversial split decision. Most of the fans, including the attending press had Rory ahead in the scoring. The San Francisco Examiner’s Eddie Mueller had Rory ahead 95-94, and the San Francisco Chronicle’s Jack Fiske had him ahead 96-92. Webb was floored in the second round by a right uppercut to the chin. His eyes were glazed when he finally made it to his feet with the aid of the ropes. Only his natural instinct and defensive skills saved him from being knocked out. When the round ended he walked to Rory’s corner and tried to sit down. Rory was the determined aggressor throughout the fight. He rocked Spider repeatedly with jolting combinations and in the tenth Spider was on the verge of going down again. Even Spider looked surprised when they raised his hand. He stated after the fight that Rory was a better fighter than when they last fought and seemed to punch even harder. [11]

Disaster struck Rory in his next fight when he met murderous punching Henry Hank of Detroit on April 25, 1959 at the Cow Palace in San Francisco. Hank was The Ring’s fifth rated middleweight and entered the fight with a record of 41-10-1, 28 by KO. Hank dropped Rory in the first round with a left hook to the head. Rory took the mandatory eight count, the last five on his feet. They slugged it out in the second round and for a while Rory was getting the better of it. But Hank unleashed a barrage climaxed by a devastating left hook. Then a left-right combination to the head put Rory on the deck. He got up, but was too wobbly to stay up. Referee Vern Bybee gave him a helping hand and called a halt at 2:50 of the second round.

Rory’s loss to Henry Hank kept him out of the ring for the longest layoff of his career. He returned on November 15, 1960 to meet old rival Joey Giambra at the Memorial Auditorium in Buffalo. Giambra boxed his way to a 10-round split-decision in what was described by the Associated Press as a top-level middleweight fight. Giambra, ranked seventh in the world, came on fast in the closing rounds after a stale start. At the final bell Giambra had Rory retreating under a hail of punches. Until then the fight was a left hand jabbing match for master boxer Giambra. Judges Lou Goldstein and Dick Fay scored the fight 6-3-1 for Giambra. Referee Lou Scozza had it 5-4-1 for Rory. From Rory’s standpoint the fight proved to him that he could still hold his own with the best middleweights in the world. And he hoped to prove it by putting all his energy into making 1961 his make or break year.

Rory couldn’t have asked for a better start to his 1961 campaign. On January 1, 1961 he squared off with Hank Casey of San Francisco, The Ring’s third ranked challenger, at the Municipal Auditorium in New Orleans. In what turned out to be the year’s first ring upset, Rory scored a 10-round split decision over Casey who entered the ring a 2-1 favorite with prospects of a title fight with Gene Fullmer in the offing. Rory came from behind to win the last two rounds and the decision. The crowd of 2,500 was brought to its feet as Rory and Casey played pitch-and-catch in several of the rounds – especially the seventh when both fighters tossed their best weapons throughout the three minutes. Casey was slow to start, but appeared to be on his way to victory going into the last two rounds. Rory checked Casey’s attack with heavy bombs to the body and head. In the final two sessions he rocked Casey with all sorts of punches. Casey, however, never once failed to meet the challenge with a flurry of blows to the head, rocking Rory with straight punches and timely uppercuts. Referee Frederick Adams had Rory the winner 5-4-1; Judge Battling Ferdie voted for Rory, 6-4; and, Judge Eddie Brown voted for Casey, 5-3-2. [12] The victory gained Rory reentry into The Ring’s monthly ratings in the tenth position.

From the very beginning of his career Rory had never shied away from fighting the iron of the middleweight division. His list of opponents was a virtual who’s-who of his era. So when he was offered a nationally televised fight at Madison Square Garden with vicious punching Florentino Fernandez just 27 days after his victory over Casey he accepted without hesitation. The 24-year-old Cuban was 28-2 with 22 KOs and possessed pure one-punch knockout power. He was ranked seventh in the welterweight division and was making his second start as a middleweight. In his middleweight debut he had knocked out Phil Moyer in five rounds.

On January 28, 1961, he and Fernandez engaged in a fairly even fight for seven rounds. Rory, cleverer at slipping and blocking punches, seemed to have a slight edge as the bout reached the eighth round. Time after time, he had rolled away from Fernandez’s hooks to the head and rights to the body. Or he had blocked such punches with his hands and forearms. Fernandez did most of the punching, while Rory fought in spurts. Twice Calhoun had staggered Fernandez – with a right to the chin in the second round and another right to the head in the sixth. But in the eighth, one of Fernandez’s left hooks thudded squarely against Rory’s jaw, just over his guard. His legs buckled, but he moved into attack, although he was staggering. Fernandez caught him again with a solid hook to the chin and amazingly Rory remained upright. Fernandez then cut loose with a rapid-fire attack, bouncing hooks and rights off Rory’s defenseless face. Finally, a left-right combination sent Rory to the canvas on his back. At the count of five, he rolled over to his knees. He got up on wobbly legs at eight. But he was so dazed that he staggered and fell into the ropes in his own corner. At this point Referee Harry Kessler called a halt at 2:31. [13] The loss dropped Rory from The Ring ratings and he was replaced by Fernandez who was elevated to the eighth spot. For all intents and purposes his status as a world class contender ended here.

Retirement is the toughest decision any athlete is forced to consider, especially if they are only 26 years old. That’s what Rory must have been thinking after his devastating loss to Fernandez. It was well known in fight circles that he was having trouble making the middleweight class limit. And at 5′ 9″ a step up to light-heavyweight would consistently put him at a height disadvantage. But in the end he decided to continue and moved up in weight to light-heavyweight.

On April 12, 1961, Rory made his light-heavyweight debut against Eddie Cotton at Civic Ice Arena, Seattle, Washington. He entered the fight at 173 pounds, the heaviest of his career. Cotton, The Ring’s tenth rated light-heavyweight scored well in the early rounds with his right hand and then continued to outbox Rory the rest of the way en route to a unanimous decision.

Despite the loss to Cotton, the fifth in his last seven starts, Rory had no inclination to retire. On September 21, 1961, he traveled to Toledo, Ohio and won a unanimous 10-round decision over former victim Franz Szuzina in his second fight as a light-heavyweight. The battle was a bloody one, with both fighters showing the effects of their rugged slugfest. Rory weighed 170 ½, while Szuzina came in at 169 ½. There were no knockdowns, but he did stun Szuzina badly with a right cross to the jaw in the seventh round and that slowed Szuzina’s aggressiveness for the remainder of the fight.

No one knows when a fighter’s next fight is one too many. In Rory’s case it occurred on November 13, 1961 against Cuban light-heavyweight journeyman Lino Rendon. Rory, 171 ¼, lasted less than two rounds against Rendon, 169. Rendon taking part in only his 13th fight landed a stiff right hand that dropped Rory in the early moments of the first round. He crashed to the canvas but was up by the count of two and took the mandatory eight count. He avoided further damage for the remainder of the round, although both fighters were bleeding from cuts over their left eyes from a head-on collision. The fans, some of whom had seen Rory perform in many of his previous 61 bouts, expected to see him storm back after his harrowing first round. But, bleeding badly from his wound he had little left. He spent most of the second round keeping out of his opponent’s reach. With about a half-minute left in the round, Rendon connected with another solid right to the head and floored him. He arose at two, but it was evident that he was in trouble as he reeled against the ropes and then almost went through them. He returned to mid-ring under his own power, but Referee Teddy Martin stepped in and halted the fight at 2:38. [14]

Despite the unexpected and devastating loss to Lino Rendon, Rory decided to give his career one more shot when he was offered a fight with talented newcomer Jimmy Ellis of Louisville, KY. Although the 21-year-old Ellis had only engaged in six professional fights he had a very successful amateur career which included a victory over Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali). Since turning pro in April 1961, Ellis had recorded five impressive victories over established veterans Arley Seifer (TKO-3), Gene Leslie (W-8), Johnny Morris (W-6), Wilfie Greaves (W-10) and Clarence Riley (TKO-2). His only loss was a 10-round decision to the crafty Holly Mims.

Rory engaged in his last professional fight against Jimmy Ellis on January 11, 1962 at the Down Town Armory in Louisville, Kentucky. Ellis, 160, needed just 1:47 of the first round to knockout Rory, 165. Ellis dropped him with two smashing right hands. He set up the knockout with a lightening left hook. After returning to his hotel, Rory announced he was quitting the ring. “I want to announce my retirement. I’m too big to be a legitimate middleweight, and I’m not big enough to be a legitimate light-heavyweight.” He further declared that it was not the knockout loss that brought him to his decision. But the fact remains that he was stopped four times in his last nine fights in which he only went 2-7. Surely he realized that if he continued he would only be an opponent for up-and-coming fighters looking to feast on his past reputation.

Rory’s wife Vivian persuaded him to move from New York to California in 1962 so he wouldn’t try to a make a comeback. Rory settled in Hollywood, CA with high hopes of becoming an actor. Rory began his new career by studying drama at “The Theatre of Arts” in Beverly Hills, California. Once he settled in Hollywood he became friends with his namesake actor Rory Calhoun and had parts in several movies, including “Requiem for a Heavyweight, “The Main Event,” and Walt Disney’s “World’s Greatest Athlete.”

In an article by Jim Murray in August 1968, he wrote: “Rory’s ambitions ran more to action movies. He’d rather be Jim Brown than John Gielgud”. [15]

Herman (Rory) Calhoun died much too young on February 15, 1988 of liver failure in a Hollywood hospital at the age of 53. According to his obituary in the Los Angeles Times, Rory was survived by his wife Vivian and his brother Fred. [16]

I wish to express my thanks to fellow IBRO members Clay Moyle, Ric Kilmer, Doug Cavanaugh, Jack Sheehan and the late Harry Shaffer for their assistance and for providing me with several sources of research material and photos included herein. DC

1. Eisenstadt, Fred, The Ring, December 1957 – Rory Calhoun Middleweight Threat

2. Newspaperarchive.com, Associated Press, April 10, 1956

3. Gallagher, Jack, Oakland Tribune, August 27, 1957

4. Newspaperarchive.com, Associated Press, November 23, 1957

5. Mullany, Jerry, The Ring, April 1958 – “Ringside Report” (page 43)

6. Newspaperarchive.com, Associated Press, August 19, 1958

7. Newspaperarchive.com, United Press International, November 22, 1958

8. Oakland Tribune, March 31, 1959

9. McGowen, Deane, New York Times, June 6, 1959

10. McGowen, Deane, New York Times, February 6, 1960

11. Thornton, Robert T., Boxing Illustrated, May 1960 – “Rings Around The World” (page 13)

12. Morales, Ike, The Ring, March 1961 – “Ringside Report” (page 53)

13. McGowen, Deane, New York Times, January 29, 1961

14. Strauss, Michael, New York Times, November 14, 1961

15. Murray, Jim, Los Angeles Times, August 8, 1968

16. Newspaperarchive.com, Associated Press, February 16, 1988